We are all born storytellers. Story defines our identity both as individuals as well as a society. It comes so naturally to invent stories. We may altogether ignore the propensity in children or we may provoke, support, record and celebrate children’s stories. Provocations can be immensely effective and one example is the use of a suitcase containing suggestive items (A suitcase of stories). An alternative is the story cube: a die with each face bearing an image that may suggest to the child the beginning of a story. These cubes are produced commercially.

Expensive blocks are not too difficult to obtain but more recently we have seen a very reasonably priced alternative. Of course, you could make your own story cube. Wooden blocks of different sizes can be purchased online. Then just burn on each face the images you prefer. Or you could purchase plain dice made of white plastic and use a permanent marker or suitable paint to scribe the required images. There is an example in the Resource Review.

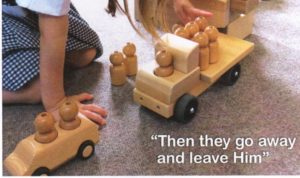

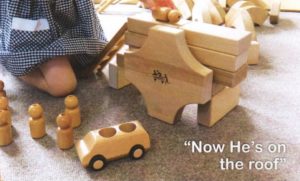

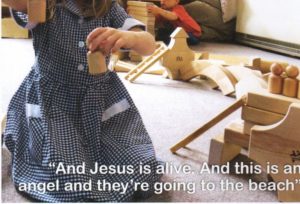

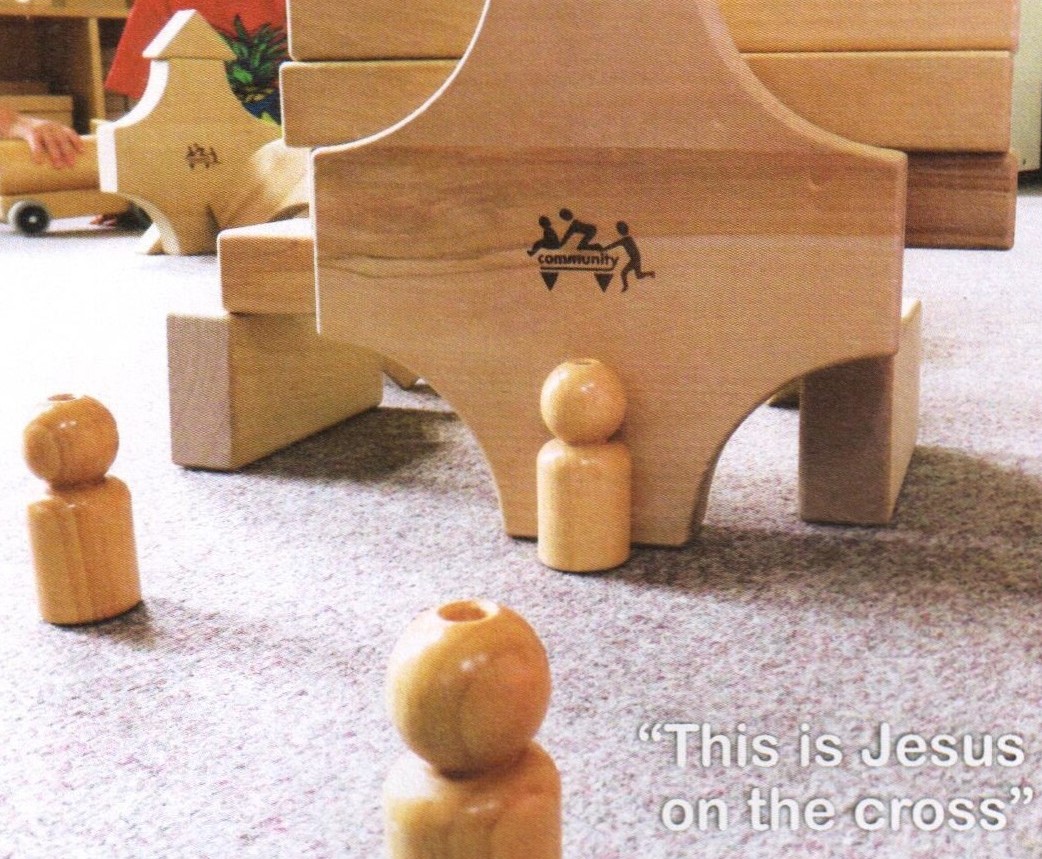

Actually, often prompts to tell stories will not be needed because children spontaneously generate them. They dress up and engage in role play, and there is a storyline. The same is the case as they involve themselves in small world activities. As they race around the woods they are escaping monsters or challenging giants. Even as they build with unit blocks there may emerge a clear narrative as with the account here. Dr David Whitebread has used LEGO in connection with primary school children’s storying and there is record of the work on the Play Learning and Narrative Skills (PLaNS) website. (1)

When children tell their stories it is important not to lose them. We need to record them in some way.

They might be:

- Audio recorded on a digital Then later on it will be possible to carefully transcribe the recording.

- Scribed as children tell If the pace of the story telling is not too fast it will be possible to jot it down as the story is told. The child may literally dictate a story. The pedagogue diligently writes showing the child how each word is written without breaking the flow of narration.

- Sketched as the stories are told. We should not feel self conscious about our artistic skills: just draw.

- Captured in photographs as with the unit block story

The records might be included in a child’s learning journal. Even an audio recording can be burnt to a CD and put in a paper CD cover stuck into a learning journal.

Then the stories can be presented as:

- a picture drawn by the child or the pedagogue

- a book compiled by the child with adult support

- a play either acted out or directed by the child The performance can be for a live audience, or captured in photographs or a video recording.

If we take seriously the proposition made by Vivian Gussin Paley that a child’s story is ” nothing less than Truth and Life”(2) then we must be committed to listening and learning from those stories. Yet they are no sooner spoken than they disappear for ever, unless we deliberately capture them. It takes determination , and readiness. It means making children’s stories a priority in our thinking and in our actual work with the little people. But how very worthwhile and rewarding because we are listening to the child’s inmost being as for a moment he reveals it.

Peter Michell

REFERENCES

1https:// www.educ.cam.ac.uk/ research/ projects/ plans/

2 Paley V G (1990), The Boy who would be a Helicopter

Harvard University Press, pl 7