Play therapy provides a place for children to express and explore their thoughts , fears and emotions in a safe child-friendly way. Instead of merely relying on words (which children can find very difficult ), the therapy uses play and creative expression as a form of communication. It is a multicultural tool that enables children to strengthen their self esteem and resilience, whilst also helping them to deal with toxic stress, trauma and fear. The essential fruits of this are children who become better emotionally regulated and balanced, more engaged in their education and able to find their place in the wider family unit.

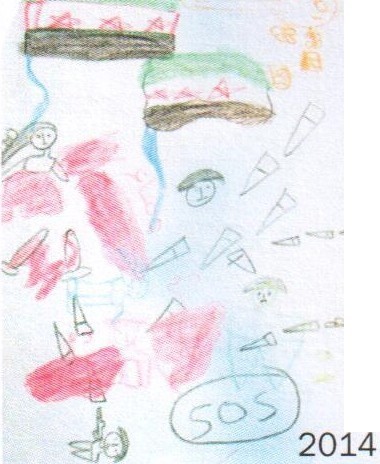

In 2014, I spent two weeks in Jordan meeting Syrian refugee families to assess if play therapy could help these children. The war in Syria has been widely reported, with many well-known aid agencies raising awareness of the impact that the war is having on children. During my visit in 2014, many parents reported how their children were suffering emotionally, having high levels of anxiety, nightmares and somatic symptoms. This was also evident from the data obtained from the Strength and Difficulties questionnaires (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997) which the parents completed.

In 2016, I decided to go back to Jordan to set up a play therapy project which formed the research part of my Play Therapy Masters study. The title of this research was, ‘To what extent can a series of play therapy sessions contribute to strengthening resilience in Syrian refugee children?’ Parents in this study (2016) described very similar emotional and behavioural problems despite many of them having been in Jordan for a much longer time than the families of 2014 who had then only recently arrived.

Play is something every child should grow up with and is referred to as the right of any child under the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child ( Fearn and Howard, 2012, MacMillan et al., 2015). Play is a fundamental right because a child’s emotional and physical well-being depend on it. Although play for each child can look different, it is something all children should have the opportunity to participate in, making it a multi-cultural experience.

What is play therapy?

Play therapy was first introduced in the 1940’s. Jordan et al. (2013) quote the Association for Play Therapy ‘s definition which is that play therapy is “the systematic use of a theoretical model to establish an interpersonal process where in trained play therapists use the therapeutic powers of play to help clients prevent or resolve psychosocial difficulties and achieve optimal growth and development ” (p.219). It has largely been influenced by Axline ( 1969) who had a strong belief that when children are given the opportunity to bring out the feelings, fears and anxieties through play, they have the ability to heal themselves. A trained play therapist uses multiple techniques such as: creative visualisation, art, storytelling, sand tray, music, dance and movement, drama therapy, puppets, masks and clay.

The healing property of play is documented with reference to refugee children who have experienced war ( Hyder, 2005 ). Research shows that children do not just forget their past, even if they are unable to express their trauma through verbal communication (Hyder, 2005, Daniel et al., 2010). Verbal communication and cultural differences may be seen as obstacles when working with children from other culture groups. In play therapy, however, the focus of communication relies strongly on play rather than on words alone.

The experience of play together with a therapeutic relationship, has the ability to reduce stress, regulate emotions, shape or re-shape brain circuits and influence future development for learning and mental health (Fearn and Howard, 2012, MacMillan et al., 2015, Stewart et al., 2016). Children’s play and play therapy are shown to reduce toxic stress, regulate a child’s feelings and increase positive brain development , all of which are important when helping refugee children adapt in positive ways despite their previous adverse experiences.

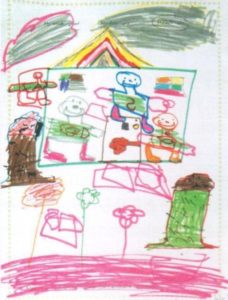

Child’s drawing of the play therapy session which she described as making her happy, 2016

The play therapy project in Jordan

The cohort comprised of twenty-one Syrian refugee children who were between the ages of six and twelve years. These children were divided into five small groups depending on their age and level of trauma . The fieldwork was conducted over a period of six months with a reputable NGO called The Middle East Children’s Institute (MECI). The majority of the children attended all ten play therapy sessions and each session was 50 minutes long.

In my work, I used culturally relevant art and play materials such as, ethnic dolls and toys which represent the children’s culture and a familiar environment (Davis and Pereira, 2014). I purchased local resources (Chang et al., 2005) such as, sand tray figures and musical instruments such as Arab drums called the ‘ta blah’. It may be argued that the most important factor of providing culturally relevant play therapy is the understanding and appreciation a play therapist has of other cultures (Hinman, 2003).

The project beginning

During the intake interviews, many parents mentioned that the children had no toys to play with or any opportunities to engage in playing with toys. All of the families lived in utter poverty. It quickly became apparent that the children were overwhelmed by all of the toys they were given access to during the first play therapy session. The children appeared dysregulated, hyper-vigilant and in a constant state of alert. Van Der Kolk (2006) and Perry and Hambrick (2008) link this type of behaviour to the experience of trauma.

I knew from the parent interviews and from comments the children had made, that daily life was full of stressful situations for many of them . From the beginning, I noticed that the children were finding it difficult to engage in activities based on their cognitive abilities which Carrion and Wong (2012) point out may be because of Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms. Therefore, crucial aspects of the project were focused on developing a nurturing therapeutic relationship (Geller and Porges, 2014), offering sensory activities (hand massage, clay and scented play dough, messy play with paint, shaving foam etc.) and rhythmic activities (using musical instruments and drums). All of which were aimed at helping children become more regulated.

The project midpoint

Halfway through , the children were calmer, more emotionally regulated, able to engage in the programme and able to interact with others in a positive way. Fearn and Howard (2012) argue that play provides children with the needed experiences for self-regulation of emotions.

The routine of each session remained the same, starting with a ‘ hello’ time, a structured activity which the children could choose whether they wanted to participate in or not, a free play time and a ‘goodbye’ time. During each session, the intention was always for the children to feel safe, have their needs and feelings acknowledged and feel appreciated and valued. For the majority of the time, the groups sat down together at the end of the play therapy session and ate their snack together.

The Project ending

Initially, the children’s focus was purely on having their own needs or desires met. Towards the end, the play therapist and translator both noticed how the children were now proud to be part of their group, and how they helped each other and at times even shared toys with each other. Careful consideration was given for the ending of the play therapy project (Oaklander, 2007 ).

Conclusion

The short-term play therapy intervention indicated a 15% decrease of emotional and behavioural difficulties using the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), a 33% reduction of post-traumatic stress symptoms using the Children’s Impact of Events Scale (CRIES), a resilience increase of 15% using the child scored Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) and a 17% increase in the parent scored CYRM . The results of this project support the use of play therapy with Syrian refugee children, provide a comprehensive understanding of how resilience was strengthened and how this was recognised by the parents, the children, the translator and myself.

Sarah Elliott